Psychological and emotional trauma can take many forms, and they affect a significant percentage of the US population, including community college students. As part of its rural health certificate program, Stone Child College (SCC), a tribal college on the Rocky Boy Reservation in Montana, offers a course on historical trauma that aims to promote individual and community healing.

“This course has helped our community, staff and students.” -Cory L. Sangrey-Billy, Stone Child College President

Historical trauma refers to the cumulative, intergenerational harm experienced by members of communities who have historically suffered from violence or oppression. In the 1980s, social worker and scholar Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart defined historical trauma as “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma experiences.”

Examining history to look forward

At SCC, the trauma-informed approach aims to help students better understand the phenomenon of historical trauma as it relates to themselves, their community, and rural health at large. The curriculum is divided into three courses: The first examines the historical context of trauma and its ongoing effects on wellness in the community; the second has students consider their personal healing journey and further explore cycles of trauma and adversity; the third uses phenomenological research, with students collecting stories from the community and exploring paths toward healing.

Ann Johnstone, human services instructor at SCC, spoke about the course and the teaching and learning goals that shape it. “The essential question from the first class is, ‘What length will a person go to survive?’” she said. “And then another question is, ‘How is this history of this painful journey still with us today?’ And then, ‘Is it possible, with that traumatic past, to heal?’”

Each of the three courses aims at a specific goal, outlined as “beliefs” in the course materials:

- Education is an effective way to heal from our historical trauma of loss of land, loss of people, and loss of family and culture. (Course One)

- Each person must take responsibility for self-healing. (Course Two)

- Healing takes place within the context of community because we are a communal culture. (Course Three)

Community health

Credits earned in the program are transferable and can apply toward degrees at four-year institutions. Students “can finish their second two years on this reservation but they’ll go through [the University of Montana in] Missoula,” Johnstone explained. Students continuing their education in rural health can do practicums within their native community while maintaining access to expanded opportunities and resources through the university.

Johnstone said that while Native Americans are by no means the only traumatized culture, in the United States they have the highest rates of adverse health conditions than any other ethnic or cultural group — a disparity that has only been heightened by the Covid-19 pandemic. In August, the CDC found that the rates of infection among American Indians and Alaska Natives were 3.5 times greater than the rates among white Americans. And in December, the CDC reported that the Covid-19 mortality rate among Native Americans was almost double that of white Americans.

While the pandemic has taken a devastating toll on communities across the country, Johnstone believes that the significant adjustments institutions have been making to accommodate remote learning will benefit rural health in the long run. “Becoming more of an online institution broadens what you can learn if you want to learn,” she said. “It’s good and bad. But I think this has really expanded telemedicine and telehealth, and that will help all rural communities.”

Culturally responsive teaching

While Stone Child College adjusts to life in a pandemic alongside other institutions and communities, the historical trauma course maintains a focus on the specific needs of the Rocky Boy Reservation and community. “Each tribe has their personal trauma,” Johnstone said. “So that’s where you start with this class, is looking at the personal.”

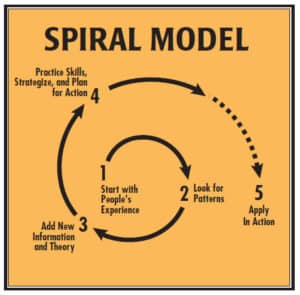

The course employs a “spiral model” for instruction, rooting the curriculum in students’ lived experiences and expanding upon those experiences to engage in culturally responsive education.

Image courtesy of TribalCollegeJournal.org

The courses also use materials written by Native American authors and scholars, including well-known works like The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and health-specific texts such as The Scalpel and the Silver Bear, about and co-written by Lori Aviso-Alvord, who was the first Diné woman surgeon in the U.S. and who combined Western medicine and traditional healing in her medical practice.

SCC faculty and staff have been encouraged to take the course in order to better understand and support their students and/or their own experience. The complete curriculum is available to read and use through the American Indian Higher Education Consortium (AIHEC) website — when she spoke with ATD, Johnstone mentioned that the Native Wellness Institute was giving a workshop at the college that week which used materials from SCC’s historical trauma course.

The title of the course, Biskanewin Ishkode in Chippewa and Iskotew Kahmahch Opikik in Cree, is a phrase that translates to, “Fire that is beginning to stand.” The phrase is a metaphor for the healing process. “The fire represents our center that’s been destroyed over the years,” Johnstone said, “so it’s exploring possibilities to make ourselves whole again.”

—

Stone Child College is one of 33 Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs) active in the ATD Network . Learn more about Stone Child College and ATD’s role in supporting student success at TCUs.