Given that nearly 95% of people currently imprisoned in the United States will be released back into society, we must ask ourselves an important question: Would we rather live in a world with citizens who have become hardened and desensitized by a system of punishment or in one that creates opportunity for incarcerated individuals to find meaning in their existence through education, hope, and a path forward for successful reintegration into society?

This summer, for the first time in nearly 30 years, broad access to Pell grants, federal grants for postsecondary education for economically marginalized individuals, were made available to currently incarcerated people. The new legislation negates the portion of the 1994 “crime” bill that barred incarcerated individuals from obtaining Pell grants and, thus, limited their access to higher education opportunities.

The restoration of Pell is an investment in American society that just makes sense. Research shows that access to higher education leads to reduced recidivism rates. Education provides opportunities for second chances. These second chances lead to jobs, which, in turn, results in more vibrant communities. Support for individuals who are impacted by the justice system should be included as an integral part of the rehabilitation process, and returning imprisoned people’s access to Pell grants is an important contribution to that much needed support.

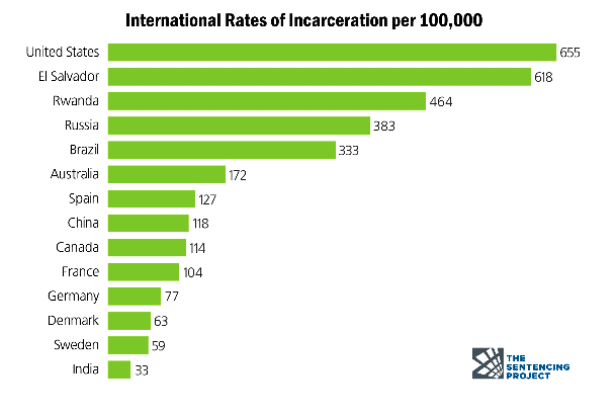

The Pell Grant restoration, however, is far from a perfect solution, and the limitations around its implementation must not go unrecognized. Higher education professionals often talk about the importance of creating equitable outcomes for all students. Yet, we have often ignored the impact that the justice system has had on racial and socioeconomic inequities — even while this system plays an enormous role in the way our society functions. For context, the United States has less than 5% of the world’s population yet holds 25% percent of the prison population. Today, there are nearly 2 million people in U.S prisons: double the number in 1994.

With imprisoned individuals’ ability to access Pell grants reinstated, long overdue attention is now being given to the role of education within the prison system. We anticipate seeing more colleges and universities creating programs to support these students. Because prisons must have a partnership with a college in order to offer accredited degree programs of which Pell access would help cover costs, the importance of these emerging college-prison relationships cannot be overstated. We, however, must take that next leap and apply what we know about equitable student outcomes in college education to college education in a prison setting. We must ask ourselves if there are systemic inequities in prisons that will negatively impact certain groups from accessing Pell grants. And the answer, unfortunately, is yes.

To understand the inequity, we must first acknowledge that minoritized marginalized people in the U.S. are far more likely to end up in prisons to begin with. Our country has a history of disproportionately arresting and sentencing people of color and those in economically marginalized communities.

In fact, The Sentencing Project finds that, at the national level, Black Americans are five times more likely and Latinx Americans are 1.3 times more likely than their white peers to be incarcerated.

Secondly, within the prison system — and even within a given prison that maintains a partnership with a college — individual incarcerated people’s access to Pell grants is not equal; racial and ethnic inequities abound. Applicants must be on the “good behavior” list, for example, and, with more Black and Latinx people more likely to be disciplined during incarceration, the odds are stacked against them. Even the ability to fill out the FAFSA form and collect required application documentation (such as previous transcripts) is hampered without internet access — a prison “privilege” that can be withheld from people who are considered to have committed an infraction.

Many of ATD’s Network colleges have been working to increase access to postsecondary education for justice-impacted individuals, even before the formal restoration of Pell. In May of this year, Achieving the Dream hosted a virtual Adult Learner Success Summit, where we highlighted the great work our Network colleges are doing to serve adult learners. Sessions during the summit covered topics on course scheduling, parenting students, data use, and other important topics related to better serving learners 25 years and older.

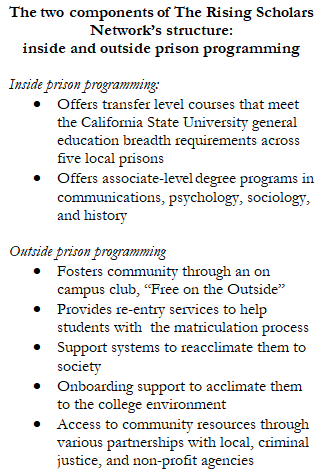

Among the topics covered was a session presented by the Rising Scholars Program at Bakersfield College in California. This session, “Support Approaches for Justice-Impacted Adults In and Out of the Carceral System,” discussed the equity-first approach to serving individuals impacted by our justice system. While this was a brief look at the supports that exist for this often overlooked student population, it started a dialogue for those in attendance on how they should explore opportunities to serve justice-impacted people’s educational needs.

Our colleagues at Bakersfield College have been part of the Rising Scholars Network since 2017, working collaboratively with other California community colleges that are “dedicated to opening opportunity and academic achievement for students who have experienced the criminal justice system.” Funding from the Network helps support initiatives across participating California colleges. The Rising Scholars program works both directly with currently incarcerated adults as well as those that were formerly incarcerated.

During their session, the Bakersfield College Rising Scholars staff encouraged us to understand that those impacted by the justice system have been marginalized, traumatized, and disenfranchised from formal education. They may have a living situation and support system that is not traditional. They face different levels of imposter syndrome, stigma, and stereotype threat. They need support with technology literacy, financial literacy, and reacclimating to mainstream society.

While we, as higher education professionals, may not have direct impact on how our country polices and detains people, we can advocate for justice reform in our own way. The restoration of the Pell grant cracks the door. We must pry that door open wider, including justice-impacted students among those for whom we work towards equitable outcomes — because until the day that inequities have been eradicated from the American justice system, supporting those impacted by the system is equity work.

- Lexi Lonas, “Prisoners now have access to Pell grant educations — but face a tough road to get them,” The Hill, July 15, 2023, Prisoners now have access to Pell Grant educations — but face a tough road to get them | The Hill